Louis E. Lomax was an important author and journalist in the mid-20th century. In 1959 he was the first African American to appear on television as a newsman.

Louis E. Lomax

Louis Emanuel Lomax was born in Valdosta, Georgia, on August 16, 1922. He was born into a prominent Valdosta black family and became influential on a broad scale himself. Louis Lomax’s grandfather, Rev. Thomas A. Lomax, (b.1863 –d.1944) was a long time pastor of Macedonia First Baptist Church, Valdosta’s first black church, organized in 1867. His uncle who raised him, Rev. James L. Lomax, (b.1898 – d.1976) was, over the course of his career, the principal of Magnolia High School, Dasher High School, and Lomax Junior High School. These were black student units of the Valdosta City School System before integration. He also was a pastor of Macedonia First Baptist church.

James L. Lomax

After his death in an automobile accident on July 30, 1970, the Valdosta Times wrote of Louis Lomax as the noted Valdosta-born writer who rose from shining shoes on Patterson Street to fame in the literary world. Lomax had moved from California, where he had been a television news commentator, to New York to be a writer in residence at Hofstra University and while there continued writing a three-volume work in Black history, society and literature.

Lomax had been on a lecture tour on the west coast and was driving cross country returning to New York when the fatal automobile accident occurred near Santa Rosa, New Mexico. His itinerary heading back to New York included attending a gathering of Valdostans in Washington, D.C., hosted by former Lowndes County Historical Society president Louie Peeples White. Louie said that she never personally met Louis Lomax, but that she did have two or three very good telephone conversations with him, enjoyed his sense of humor, and all involved were looking forward to the Washington, D.C. function.

In 1968 Louis Lomax was the first African-American to make a principle address to a Valdosta State College audience. The above photo is of Dr. Marvin Evans and Louis E. Lomax at VSC in 1968. From the Campus Canopy, October 11, 1968. Courtesy of VSU archives. Louis Lomax’s relatives are buried in northeast corner of Sunset Hill Cemetery—very near Valdosta State. ____________________________________________

In 1968 Louis Lomax was the first African-American to make a principle address to a Valdosta State College audience. The above photo is of Dr. Marvin Evans and Louis E. Lomax at VSC in 1968. From the Campus Canopy, October 11, 1968. Courtesy of VSU archives. Louis Lomax’s relatives are buried in northeast corner of Sunset Hill Cemetery—very near Valdosta State. ____________________________________________

Lomax’s interview with Malcolm X

Louis Lomax became the first African American to appear on television as a newsman in the documentary “The Hate that Hate Produced.” The series was presented by Lomax and Mike Wallace on Wallace’s program Newsbeat in five segments from July 13 to 17, 1959. Mike Wallace went on to fame at the CBS television network. Lomax told Wallace about the Nation of Islam earlier in 1959. Lomax, as an African American, was given rare access to the organization. Accompanied by two white camera operators, Lomax conducted interviews with the Nation’s leaders and filmed some of its events. The program was the first time most white people heard about the Nation, its leader, Elijah Muhammad, or Malcolm X, both of whom were interviewed by Lomax for the program.

Louis Lomax interviewing Malcolm X in 1959

Columbia University has a website featuring the Malcolm X Project Journal that includes audio/visual clips of the documentaries. Also on this site is an audio/visual tape of actor Ossie Davis who performed a few years ago with the Valdosta Symphony. Ossie Davis was born in nearby Cogdell. Georgia and died in 2005. Lomax also wrote a book dealing with Malcolm X and his political movements titled When the Word is Given, however, we unfortunately do not a copy of this book at the museum.

___________________________________________

Lomax Books in Our Museum

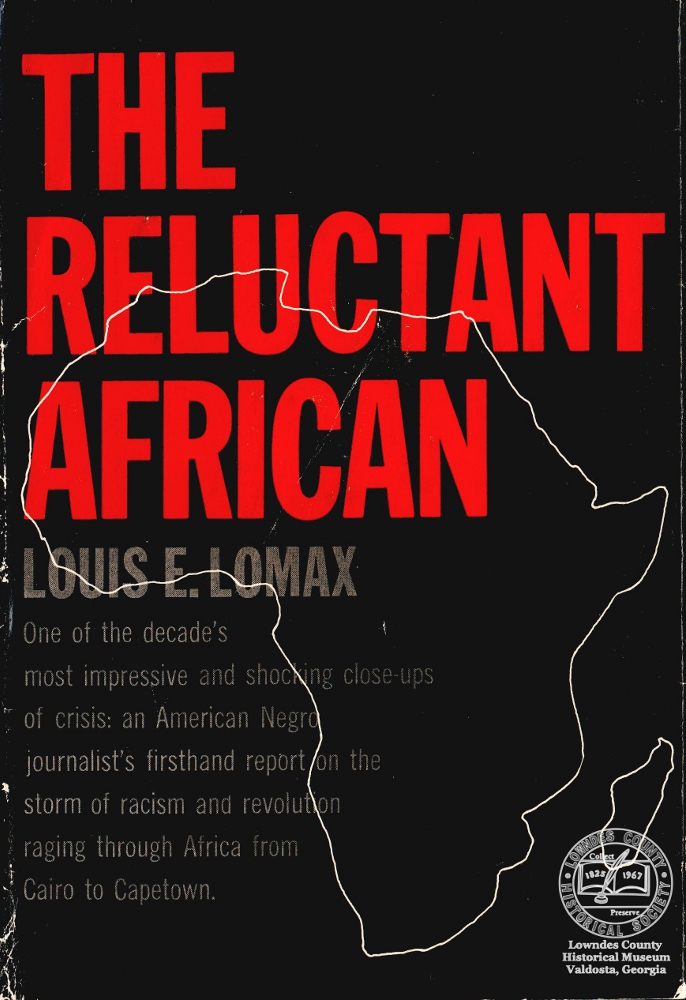

The Lowndes County Historical Museum is fortunate to have copies of two of Lomax’s other books, The Reluctant African and The Negro Revolt. Below are descriptions from the inside covers of both books:

After visiting the continent of Africa, Louis Lomax wrote the book, The Reluctant African. It received the Saturday Review Anisfield-Wolf award in 1960 for a book dealing “most creditably with social and group relations.”

Topics and issues he writes about are condensed in the following overview that gave information on the book.

Cover of Lomax’s The Reluctant African

The Reluctant African

By Louis E. Lomax

The Reluctant African is an American Negro’s subjective report on the people and forces now at work in Africa – a story no white reporter could get. It is a disturbing account of African affairs based upon privileged talks with the men who plot Africa’s tomorrow.

In this fast-moving and dramatic first person, account you—

- Watch as reporter Lomax is “de-Americanized” and “de-Negroized” by African nationalists –the prime prerequisite for his trip.

- Hear top government spokesmen in the United Arab Republic discuss frankly how they have created the “black brotherhood” a mystique based on hate of everything “white.”

- Learn how the U.A.R.’s President Nasser gave the Communists their first foothold in Africa and then turned against them when it suited his purposes.

- Talk with African politicians exiled in Egypt and discover how they get money from the East, the West and Communist china.

- Come face to face with the harsh facts behind the nonalignment doctrine now sweeping Africa. Attend the second annual Conference of Independent African States, in Ethiopia: listen as Haile Selassie, long a staunch supporter of the West, delivers a nonalignment speech; during a carefree embassy party, witness evidence of the incredible anti-American attitudes now sweeping Africa; feel the agony of a Negro reporter who wants to defend his country but knows this act would make it impossible for him to get further inside interviews.

- Feel what it was like to be Negro American traveling along the rim of the Congo during the revolt against the Belgian settlers; go inside embassies and air terminals and watch a Negro American being mistaken for a Congolese; feel the bitterness; listen as only a fast explanation by an embassy receptionist saves the American from an almost certain mauling by angry Belgians.

- Meet with African politicians in Southern Rhodesia.

- Sit at the tables with the Africans as they plot the moves that led to the recent race riots in Salisbury.

- Go on a cloak-and-dagger expedition as reporter Lomax outwits South African authorities and contacts the African underground inside South Africa. Hear the shocking story surrounding the “disappearance” of thirty thousand Africans since Sharpeville; realize the naked meandering of the Bantu Education Act.

- Reporter Lomax finds against both the whites and the blacks in Africa. The title of his book indicates his reluctance to identify himself with Africa’s drive for “black supremacy” since he has spent his life fighting not only “white supremacy” in the U.S., but he whole idea of racism.

____________________________________________

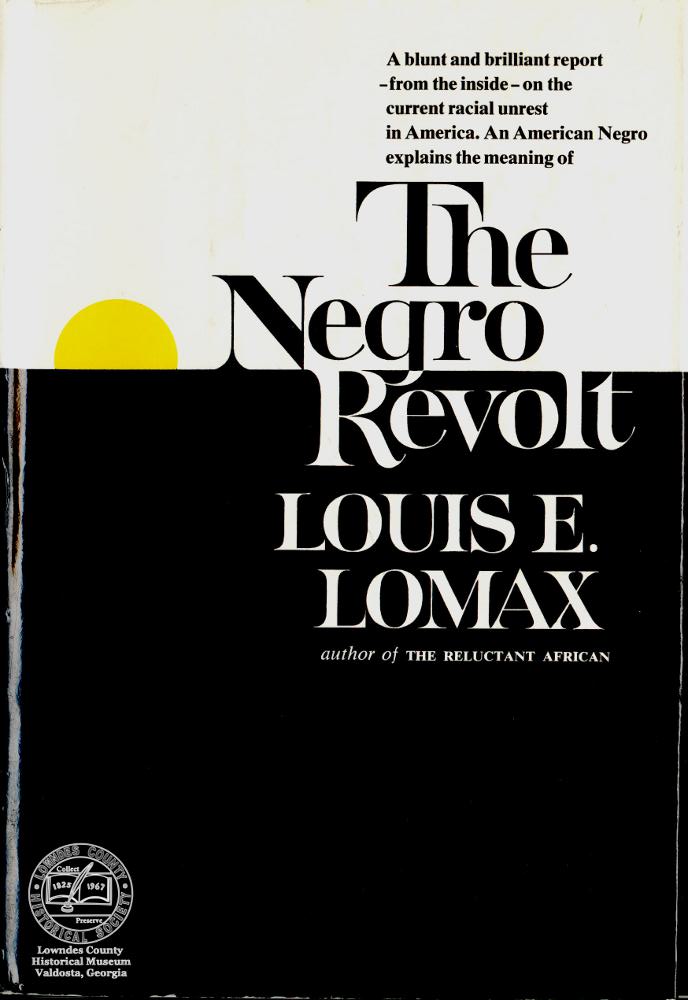

In 1962, Harper & Row published The Negro Revolt by Louis Lomax. The book cover’s description of the book is included here. Also included is his mention in the book of his grandfather, Rev. Thomas Lomax and of his uncle Rev James L. Lomax.

Cover of Lomax’s The Negro Revolt

The Negro Revolt

By: Louis E. Lomax

Here is an American Negro’s comprehensive and informed report on his people’s mood of militancy and a searching examination of the reasons for it. The award-winning author of The Reluctant African explains that the current Negro revolt is directed not only against the white world but also against the entrenched leadership of the old-guard Negro organizations. In the process of explaining this twofold revolt, Mr. Lomax takes a searching new look at American history and examines Negro leadership organizations in detail.

This is a book of facts: you will learn who runs the old and new Negro leadership organizations, where they get their support, what their goals and problems are. This is a book of personalities: Mr. Lomax gives candid profiles of Negro leaders from Martin Luther King to Elijah Muhammad, and reveals the feelings of the Negro man-in-the street. This is a book based on personal experience: the reader will visit a Southern church during a revival meeting, sit in on a press conference with Martin Luther King, watch a Harlem street-corner speaker inflame a crowd against the white man. The Negro Revolt explains the current wave of racial unrest in terms of people, revealing the humans passions and strivings that lie behind the headlines. This is the story of one of the most troubling problems of our times, seen from the inside.

Dr. Martin Luther King is the son of one of the most imposing men I have ever met in my life. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and the Reverend James L. Lomax (my uncle, but the person who took over my rearing when I was ten years of age and bore all the responsibilities for my education) are fellow Baptist ministers in Georgia and have been colleagues in the Baptist State Convention for thirty years. As a youth, I attended every session of the convention, aw well as those of the auxiliaries, and got to know Dr. King, Sr. rather well. He is a powerful preacher, a brilliant church politician, and is of dying order of Negro clergymen who have the uncanny ability to make people do things by the sheer poser of their presence and oratorical ability. Martin Luther King, Sr. was, and is what we used to call a “hard” preacher. That is to say, on Sunday morning he preaches as if Heaven and Hell were coming together and only he, sustained by the god-given power of oratory, could keep them apart.

____________________________________________

Reflecting on Life in Georgia

Georgia Boy Goes Home is one of about twelve articles that appeared in the April 1965 issue of Harper’s Magazine. It was part of a special supplement of “The South Today, 100 Years After Appomattox.” The writers included the likes of C. Vann Woodward, acclaimed historian, and James J. Kilpatrick who became well known as a debater on the CBS 60 Minutes Show. This magazine was in our wonderful files at the museum. I remain amazed at all the printed material that Albert and Susie, with help from others, collected over the years, and at the richness of Lowndes County history these files reveal to us. Several excerpts from the article are in this newsletter under separate title; others are printed here:

GEORGIA BOY GOES HOME

By Louis E. Lomax

Louis E. Lomax has been an acute observer of the Negro revolt in his many books and articles. From the moment he met Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Atlanta airport to the day he gave the sermon in his uncle’s church in Valdosta, he was struck by the uneasy juxtaposition of intransigence and change in his native land. What emerges is an intriguing portrait of a Southern town.

There are other changes. The new freeway that runs from Atlanta to Jacksonville has ruined the sucker and catfish hole where grandfather and I used to fish…..The mud swamp on Clyattville Road is now the airport, and the dasher High School from which I graduated twenty-five years ago is now the J. L. Lomax Junior High School, which is named after my Uncle James. When I walked these streets as a boy, I prided myself in the fact that I knew exactly how many people there were in town – 14,592. My grandfather used to say that this figure included “Negroes, white people, chickens, cows, two mules, and a stray hound dog.”

. . . As far as public accommodations go, Valdosta is an open town. I ate where I chose and went where I pleased, talking with whomever I wished of both races. Like most Southern towns, this one had moments of racial tension during the first days on integrated cafes, lunch counters, and theaters. But well-disciplined law force invoked the law of the land. While police chiefs in other Southern towns were rousing the white rabble, the Valdosta police chief was traveling through the swamp farmlands on the town’s outskirts telling white men who were most likely to get liquored up and come to town to keep calm. The Negroes were told to eat, not just demonstrate, and the whites were warned to keep the peace. They both did just that. Whenever and wherever Negroes have pressed their case there has been compliance with the Civil Rights Act.

. . . A loosely organized interracial council arrived at reasonable, step-by-step goals. I think the major preventive act took place when the white power structure yielded to demands for Negro policemen. The sight of Negroes whom they knew and trusted policing their community gave Valdosta’s Negroes a pride and a sense of personal security they had never had before. My town has not made ugly national and international headlines, because the white power structure, led by three key men, took a long look at the turmoil that confronted so many places in the South and decided it would not happen in Valdosta.

Lomax wrote of the late Comer Cherry and his efforts on the bi-racial commission. Albert Pendleton said Cherry’s wife Frances also worked effectively with the group. Lomax wrote, “Cherry has been president of the Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club, and a prime mover behind the bi-racial commission. He is representative of the new thinking among white Valdostans.” Lomax once quoted Cherry as saying, “The way I see it, the economy of the Negro community is the root of the problem. Once the Negro can earn a respectable pay check, most of the agitation will die down.” There are many other segments in Lomax’s article “Georgia Boy Goes Home” than are covered in this newsletter. If you want to see the entire article we have the magazine at the museum.

The Atlanta Airport Layover and Dr. Martin Luther King

Excerpted from “Georgia Boy Goes Home” Harpers Magazine, April 1965.

I came home to Georgia by jet. The flight from New York to Atlanta was uneventful, but as the plane taxied toward the terminal, I felt slightly uneasy. Georgia had just gone for Goldwater; Georgia was still Georgia. Walking along the corridor to the main lobby, I heard cracker twangs all about me; these, in my childhood, were the sound of the enemy, so that even now I react when I hear them, and I immediately suspect any white man who has a Southern drawl. Yet I could see no signs telling me where I should eat, drink, or go to the rest room. The white passengers seemed totally unconcerned with me. I could see a change in their eyes, on their faces, in the way they let me alone to be me.

I was on my way to the southern Airlines counter to confirm my reservation to Valdosta. Suddenly I saw a brown arm waving at me from a phone booth. There in the booth, was Martin Luther King, Jr. Martin’s family and mine had been Negro Baptist leaders in Georgia for almost fifty years; I first got to know him when I was in college and was in Junior high school. Now I was on my was home to Valdosta for Harper’s to write about the changes in my town and to give a sermon in my uncle’s church; Martin was on the way to the island of Bimini to write his Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

Martin and I stood in the lobby and tried to talk, but to no avail. We were continuously interrupted by white people who rushed over to shake his hand and pat him on the back. I could hardly believe that I was in Atlanta, that these were white people with twangs, and that they were saying what they were saying. Many of them asked for Martin’s autograph; a few of them recognized me from television or from the dust jacket of a book and asked me to sign slips of paper. They were an incredible lot: a group of soldiers, five sailors, three marines, a score of civilians including the brother of the present Governor of Georgia, and three Negro girls. On stately old white man walked up to Martin and said, “By God, I don’t like all you’re doing, but as a fellow Georgian I’m proud of you.”

My flight home was several hours away, and I had made a reservation at a motel near the airport. As Martin and I were parting, the loudspeaker announced that the motel bus was waiting for “Dr. Lomax.” A Negro porter gathered my baggage and led me to the bus; he put my bags on the ground and I tipped him. A few seconds later, I saw the white bus driver, and I knew I had reached a moment of confrontation. It seemed an eternity as I glanced up and down, from the white driver to my baggage: I remembered all those years I had spent serving white people as a bellhop, a shoeshine boy, and a waiter. The driver, however, couldn’t have cared less about me or my color. He picked up my bags and put them in the bus. This is what the Republic has done to me and twenty million like me—I never felt so equal in all my life when I saw that white man stoop down and pick up my bags. “Get right in sir,” he said.

The motel people were the same. They acted as if there had never been such a thing as segregation and I ate and drank where I pleased.

____________________________________________

The Sermon at Macedonia First Baptist Church

Lomax’s family had strong ties to Macedonia First Baptist Church

Louis Lomax included his visiting and preaching at Macedonia Baptist church in his article “Georgia Boy Goes Home”. His grandfather, Reverend Thomas Lomax and his uncle, Reverend James L. Lomax, who raised him, were both long time pastors of the church.

“The next day I stood in the Macedonia Baptist Church pulpit that has been occupied by a Lomax for more than half a century; some of the people who sat in the congregation had known me before I knew myself. Tribal middle-class pride was running high. Just the Sunday before, Calvin King, one of my younger childhood schoolmates who went on to get his doctorate in mathematics, had been the guest preacher. Uncle James had listened with pride as Calvin told of his travels in the Holy Land, of his work in helping launch a new university in Nigeria. I told the congregation about my experiences in Africa, behind the Iron Curtain, and in American cities where racial troubles had erupted. White Christianity, I said, had become synonymous with white oppression all over the world, and the black Christians were about all Jesus had left. We were the only ones who could now go about preaching the words of Jesus without being suspected of questionable motives. My plea was that we black Christians become more militant, that we take a courageous stand for human rights, to clarify Christ’s name if for no other reason. It is significant that when I had finished there was a loud congregational “amen.” A few white people had come to the service, and one of them was crying. Uncle James issued the invitation for the unchurched to come up and join. But that was not the hour for sinners. Rather, I think, it was a time for the believers to reassess what they were in for.”

____________________________________________

Lomax Searched for King Case Facts

Louis Lomax was interested in searching out the events of the Martin Luther King, Jr. case. His stories about his search were published by the North American Newspaper Alliance chain. The Book, The Taking of America, 1-2-3-, updated 3rd Edition 1985, by Richard E. Sprague, gives explanation of the North American Newspaper Alliance and tells of Lomax’s stymied efforts in tracking King Case details. This newspaper chain, with papers affiliated is small communities through the northern and eastern U.S. supported the Warren commission findings, as did all the other major newspaper services and chains. The Alliance also became involved in the Martin Luther King case and it circulated the syndicated column by the black writer and reporter, Louis Lomax, who had taken an interest in finding out what really happened in the King assassination.

Lomax located a man named Stein who taken who had taken a trip with James Earl Ray from Los Angeles to New Orleans. The two retraced the automobile trip of Ray and Stein beginning in Los Angeles and heading through Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. They were trying to find the telephone booth from which Ray had called a friend named Raoul in New Orleans somewhere along the route. Raoul, according to Ray, was the man who actually fired the shot that killed King. Stein remembered that Ray told him he was going to meet Raoul in New Orleans and that Ray phoned Raoul at someone’s office. Stein couldn’t remember exactly where the phone booth was because he and Ray had been driving non-stop day and night.

Lomax wrote a series of articles depicting Raoul as the killer and Ray as the patsy. He sent them to the Alliance, a column each day, from the places along the retraced trip he and Stein took. Finally, Lomax’s column announced that they had found the phone booth at a gas station in Texas and that he was going to obtain the phone number Ray had called in New Orleans. He presumably was planning to visit the local telephone company office the next morning and obtain the number. That was the last Lomax column ever to appear in the North American Alliance papers. He seemed to disappear completely. The readers were left hanging, not knowing whether he obtained the phone number of whether he discovered who it belong to. The committee to Investigate Assassinations located Lomax several months later and asked him what had happened. He said he had been told by the FBI to stop his investigation and not to publish or write any more stories about it. He said he found the phone number and where it was located in New Orleans. He gave the number to the Committee to Investigate Assassinations. He said he was afraid he would be killed and decided to stop work on the case.

Whether North American Newspaper “Alliance management knew about any of this remains unknown. What is known, however, is that Louis Lomax died in a very mysterious manner in 1970. He was traveling at a very high speed and was found dead in a car crash, according to the State police report. Lomax’s wife says he was a very careful driver and never drove at high speeds.

____________________________________________

Lomax and the FBI

The Freedom of Information – Privacy Act now allows access to Federal Bureau of Investigation records. The file on Louis E. Lomax is over 150 pages. It consists of letters, telegraphs, FBI inter-office memos, newspaper clippings; copies of speeches and several sheets headed FBI Deleted Page Information Sheet. These have a code number that gives the reason why particular pages are not made public. The late 1950s and the1960s cover an interesting time in the Civil Rights movement and spread of Communism.

One item from 1964 in the FBI files is a letter to J. Edgar Hoover telling what Louis Lomax had said to some Lutherans meeting in convention at Detroit, Michigan. The name of the writer of the letter is blotted out for the public file. The write states that Louis Lomax said: “Everybody today is so busy looking for communists, looking for left-wing bugaboos under bedspreads, that when we (blacks) walk down the street and say ‘I want a job,’ it (the reply) is immediately heard … ‘the communist did that!’ We stage a sit-in in order to get a cup of coffee, or to go to the bathroom, and we’re accused of being communist inspired. What a pity it isn’t (called) Christian inspired. And when Mr. J. Edgar Hoover, who hasn,t been able to find a single bomber – although 69 bombings, 23 of them churches, have occurred against my people in the past four years – J. Edgar Hoover hasn’t found a cotton pickin’ one of them, yet he has found communists in the Civil Rights Movement. Bully for him!” After the reporting of this Lomax speech to the FBI, the FBI did prepare a report on the few bombers that had been caught. This information is also in the FBI file. Another item in the FBI files is an October 4, 1963 document concerning Louis Lomax’s passport file review. Lomax was being sent to Cuba by Harper’s Magazine to do an interview with Fidel Castro. This FBI file reads: Louis Emanuel Lomax On September, 1963, a review of the passport file, United States Department of State, pertaining to Louis Emanuel Lomax, revealed he was issued Passport Number 2181534 on May 27, 1960. In applying for this passport on May 27, 1960, at New York, New York, he furnished the following information:

Birth data: August 6, 1922, Valdosta, Georgia

Permanent residence: 114-29 166th Street, Jamaica, 34, New York

Father: Emanuel C. Smith, born Sandersville, Georgia, date not known

Mother: Sarah Louise Lomax born Valdosta, Georgia, date not known

Wife: Married on February 5, 1958, to Beatrice Louise Lomax, born may 17, 1934, St. Louis, Missouri

Proposed itinerary: Depart New York City on June 15, 1960 by air for one-month vacation in England and France

Physical description: 5’ 9”, black hair, brown eyes

Occupation: Writer

____________________________________________

Lomax Papers

The Louis E. Lomax papers are housed in the Ethnicity and Race Manuscript Collection at the University of Nevada at Reno, University Library. The collection is listed as fifty cubic feet, unarranged. It includes manuscripts, correspondence, and legal and financial materials collected or created by Lomax. Three days advance notice is required for use of the collection.

____________________________________________

Lomax Time Line

1922: Born in Valdosta, Georgia, August 16, 1922. Mother died August 25.

1959: Louis Lomax and Mike Wallace interview Malcom X and Elijah Mohammed in a television documentary broadcast in five segments from July 13 to 17.

1960: His book, The Reluctant African after visiting the continent of Africa.

1962: Book, The Negro Revolt, is published

1964-68: News commentary show, KTTV, Channel 11, Los Angeles, California 1965: Visits Valdosta and writes a article “Georgia Boy Goes Home”

1968: October, featured lecturer at Valdosta State College

1970: Dies in automobile accident.